|

|

Dr. MJ Bazos MD,

Patient Handout

Adolescence: A 'Risk

Factor' for Physical Inactivity

Exercise is good for your health-a lesson

learned from the ancients-but the recommendations for achieving such benefits

has undergone a significant transition in the closing decades of the Twentieth

Century. Most particularly, there has been a shift away from the importance of

developing cardiovascular (aerobic) physical fitness and toward the promotion of

life-long physical activity. This change has resulted from an understanding that

the biological mechanisms linking exercise to health are not simply related to

achieving high cardiovascular function but also in increasing caloric

expenditure (obesity), weight-bearing activities (osteoporosis), and muscle

strength (back problems, physical incapacity in the elderly).

In addition, it has been recognized that most

diseases affected by exercise (such as coronary heart disease, hypertension,

obesity, and osteoporosis) are a result of life-long processes, surfacing

clinically in the older adult years. This observation has prompted an emphasis

on promoting exercise habits in children and adolescents as the starting point

of a life-style of regular exercise that will be maintained through to

adulthood. That is, the introduction of exercise early in life with the key

issue of persistence of activity has replaced an emphasis on improving physical

fitness to threshold levels.

This shift in the exercise-promotion paradigm

necessitates a parallel change in focus toward behavior modification rather than

exercise training. But in developing this strategy many questions have arisen.

How can young people best be "turned on" to being physically active? Can it be

truly expected that improving activity habits of an eight-year old girl will

cause her to be a more active adult? Given programmatic and financial

constraints, should the promotional focus be on certain populations of children

who are at particular risk for a sedentary lifestyle (the obese, the athletic

"failures")? Or should physical activity promotion be expanded to the pediatric

population at large?

One particularly critical aspect of activity

promotion for lifetime health surrounds its timing. It might be assumed that

there are certain periods of development when efforts to introduce physical

activity habits are more likely to 1) be successful, 2) create an optimal

salutary effect on health risk, and 3) be sustained into adulthood. In fact,

when guidelines for physical activity for children have been created, special

attention has been focused on age-specific recommendations. There has been a

growing recognition that the adolescent years may, in fact, serve as such a

pivotal, critical period for activity promotion and particular guidelines have

been suggested for this age group (Table 1). Epidemiologic evidence suggests

that levels of activity demonstrate a particular decline during the teen years,

especially in females. Adolescence is a key period for changes in certain health

risk factors such as the appearance of the initial lesions of coronary artery

disease and peak development of bone mineral density. Standing at the immediate

threshold of adulthood, the adolescent's physical activity habits-as well as

health risk factors-are more likely to track into the older years. Opportunities

for participation in organized sports decrease in the teen years, while factors

discouraging physical activity, such as access to automobiles, become more

available. Increases in body fat in the female at puberty may serve to

discourage participation in physical activities. The biological drive for

physical activity wanes during adolescence at the same time that increasing

independence allows teenagers to manage their own lifestyles. They are thus less

influenced by parents and more by their peers, and motivation for physical

activity depends more on social rather than biological or family

factors.

Table-1.

Physical Activity Guidelines for Adolescents

These unique features of adolescence provide

both risk and opportunities for exercise-health promotion. The following

sections will examine these influences which affect the present and future

physical activity of adolescents. Recognizing and understanding these factors

may prove essential in developing strategies for exercise promotion at this

critical period in life.

Physical Activity in Adolescence

Efforts to improve exercise habits in the population confront the clearly-established trend for a progressive decline in individual physical activity throughout the life span. The daily caloric expenditure (relative to body size) of an 18-year old is approximately half that of when he/she was 6 years old. (This is confirmed by life's experience: consider the Brownian motion of a group of kindergarten children at a birthday party compared to the same individuals at their high school graduation reception.) Reviewing research data has concluded that during the school-age years, daily physical activity decreases at a rate of about 2.7% per year in males and 7.4% per year in females. Levels of activity steadily decline during the adult years as well. The percentage of adults in the United States who are sedentary generally increases 2-3 fold between the ages of 20 and 65 years. It appears that this basic trend for declining

activity during life has a biological basis. Evidence supports the presence of

an inherent control center within

the central nervous system which governs levels

of activity. With increasing age, centrally-dictated caloric expenditure through

activity declines, paralleling that of basal metabolic rate. The decline in

physical activity with age is therefore largely intrinsic, the result of a fall

in central drive as well as other biological factors, such as a decreasing

skeletal muscle mass in older years. There is no question, however, that the

shape of the physical activity-age curve, i.e., the rate of decline in activity,

is influenced by extrinsic, or modifiable, factors. And this is where

interventional strategies can be effective in improving habits of physical

activity. Critical to this approach is the identification and manipulation of

psychosocial and environmental determinants which affect the individual's

motivation and participation in physical activity.

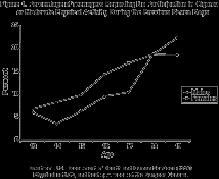

Evidence exists to suggest that the rate of

decline of physical activity is particularly accentuated during the teenage

years. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicated that 81% of boys in grade 9

participated in vigorous activity during 3 or more days in the week before the

survey. This proportion decreased steadily during the high school years to only

67% in grade 12. Between the ninth and twelfth grades the percentage involved in

such vigorous activity in girls fell from 61% to 41%.

The survey also revealed a downward trend in

enrollment in physical education during the course of high school. In the ninth

grade, 81% of females and 81% of males were participating in physical education.

By their senior year, however, these numbers had fallen to 39% and 45%,

respectively.

Another study reported that 11-13 year old Irish

boys participated in an average of 33 minutes of activity daily while those

14-16 years were active only 7 minutes a day. In females, mean values were 20

and 12 minutes, respectively. Another study used accelerometers to examine the

relationship of sexual maturation and daily activity levels during adolescence.

Average daily movement, expressed as counts per minute, was 30% less in the

postpubertal compared to midpubertal boys. In girls, counts were 19% less at

postpuberty compared to midpuberty.

Yet another study involved 233 Dutch male and

female teenagers using heart rate monitoring to assess activity. At age 12-13

years the boys and girls spent 1.3 and 1.2 hours per day, respectively,

exercising at an intensity equivalent to 50% VO2max. By age 17-18, time had

decreased to 0.5 and 0.8 hours per day, respectively.

It is not difficult to suggest explanations for

this inordinate decline in physical activity during adolescence. A combination

of intrinsic and extrinsic factors are juxtaposed during the teen years which

make the adolescent particularly vulnerable to developing a sedentary life

style.

The Decline of Biological Drive and Rise in

Psychosocial Influences

During early childhood, daily energy expenditure through physical activity appears to be largely biologically-driven. That is, the three year-old who zips about the house does not make a conscious decision to exercise or not. At this age, motivation for physical activity, access to exercise facilities, and support of family members are generally not critical to level of habitual physical activity. As the child grows, the biological drive for exercise energy expenditure declines and extrinsic factors affecting activity levels become more influential. This reaches a particularly critical point at adolescence, when the diminished inherent drive for activity coincides with increasingly important psycho-social factors which influence involvement in physical activity. Unfortunately, these extrinsic factors often act negatively to diminish activity levels during the teen years. The motivation for physical activity for the

typical adolescent, no longer a biological issue, is shaped by factors that

involve peer acceptance, physical capabilities, sexual attractiveness, and

self-concept. For the talented high school athlete, sports play satisfies these

issues. But for the non-athletic teenager, physical activity may be the

antithesis of these goals, which are met by "hanging out", rebelling from adult

forms, and adopting strange dress or hair styles. For many teenagers, vigorous

physical activity is simply not "cool."

These social barriers to regular physical

activity are compounded by the growing need for independence with rejection of

adult-oriented health goals. The adolescent becomes old enough to drive, has

more money and access to fast foods, and increases exposure to cigarette smoking

and drugs. All these factors combine to make regular physical activity and other

healthy lifestyles unattractive options for many adolescents.

Gender and Body

Composition

Epidemiologic studies consistently indicate that males are involved in more total and vigorous daily physical activity compared to females, and this is true during adolescence as well. In addition, as noted above, some reports suggest that the decline in habitual physical activity during the teen years is more exaggerated in girls. These data imply that adolescence may be a particularly high risk period for developing sedentary habits in females. Females face social pressures that have

historically linked physical prowess and athleticism to maleness, and gender

differences in activity have traditionally been accounted for by perceptions

that femininity is not consistent with vigorous activity and sports play. While

significant progress in dispelling this concept has occurred, detrimental ideas

concerning gender-appropriateness in sports play and physical activity persist.

Social issues continue to act as important impediments to involvement in

exercise by girls. In adolescence these influences are compounded by the

burgeoning sexuality at puberty and strong desire for attractiveness to the

opposite sex. In males, sexual desirability is often linked to physical

capabilities in sports participation and physical activity. In females, on the

other hand, attractiveness is focused on physical features, often perceived as

incompatible with vigorous physical activity.

Inevitable changes in body composition at the

time of puberty may also work to the adolescent female's disfavor. Rising

estrogen levels in the early teen years promote an increase in body fat in

females, while the androgenic influences of puberty augment muscle mass in

males. A typical 8-year old girl has 16% body fat, while at age 14 she will be

22% fat. The value will rise to 24-30% by the time she is 35 years old. This

increased fat serves as an inert load that must be transported during

weight-bearing physical activity. That makes exercise more difficult, causing a

tendency to avoid physical activity, which in turn results in increases in body

fat and diminished physical fitness. The end result of this cycle is entrenched

sedentary habits in the young female during the teen years which are difficult

to reverse.

Limited Access to Sports Play

Participation in organized sports activities is

a valuable means of maintaining high levels of physical activity in a social

setting. During the elementary and middle school years, widespread involvement

by youngsters in community sports teams such as soccer, swimming, and baseball

has, in fact, permitted large numbers of otherwise athletic-unskilled children

to become physically active. Once high school is reached, however, such

"everybody plays" programs disappear, supplanted by highly competitive programs

which are designed for the few who are sufficiently skilled to "make the team".

Opportunities for intramural participation in high schools is also unusual, as

financial constraints channel available funds to inter-scholastic

programs.

Adolescent Physical Activity and Health Risk

Factors

An improved understanding of the natural course

of certain chronic diseases of adulthood has indicated a particular significance

for health interventions during adolescence. Many of these diseases are outcomes

of pathological processes which begin during the teenage years. It follows

logically, then, that interventions designed to prevent or reduce the risks of

these diseases are best introduced during adolescence. In addition, given the

proximity of adolescence to the adult period when such diseases appear

clinically, behavioral changes such as improved physical activity in teenagers

should have the best chance of tracking into the adult years.

Several examples highlight this strategy.

Osteoporosis, or decreased bone density, increases susceptibility to skeletal

fractures and is a major cause of disability and death in elderly individuals,

particularly women. The peak gain in bone mineral density occurs at 13-14 years

of age, and 90 percent of adult bone mineral content is established by the end

of adolescence. As weight-bearing activity stimulates bone growth, regular

exercise during the teen years should be expected to be important in decreasing

the incidence and severity of adult osteoporosis.

In adults, the risk of coronary artery disease,

the major cause of death in the United States, is reduced by both regular

physical activity and increased physical fitness. This may occur from an

ameliorating effect on coronary risk factors, particularly elevating

HDL-cholesterol, or by some unknown direct effect on the coronary vasculature.

The atherosclerotic lesions which lead to coronary artery obstruction in adults

appear initially in these vessels on autopsy specimens of adolescents. Physical

activity habits which can reduce the risk of future myocardial infarction are

therefore optimally introduced during the teen years.

Obesity in adults carries an increased risk of

atherosclerotic vascular disease, hypertension, stroke, type 2 diabetes, and

other significant diseases. Since obesity in children and adolescents rarely

causes medical complications, the risk for the overweight youngster lies in the

chance that his or her obesity will carry over into adulthood. As would seem

intuitive, the risk of doing so increases with age during childhood, such that

the obese adolescent has an 80% chance of becoming an overweight

adult.

Tracking of Physical

Activity

The strategies in this discussion are based on

the premise that physical activities initiated during adolescence will persist,

or track, through the adult years. The extent that this is true has not yet been

well clarified. Studies investigating this question are hampered by lack of an

accurate means of measuring physical activity in large populations, an inability

to easily assess intensity of regular exercise, and the effect of significant

subject drop-out on study-findings.

One study described correlation coefficients of r=0.64 and 0.48 for women and men, respectively, between physical activity (by questionnaire) at age 16 and 27 years of age. In a similar study, it was found that leisure time activity at age 16 years in males decreased the risk of being sedentary at age 34 years by one-half. A Metanalysis concluded that these reports "indicate that physical activity and sport participation in childhood and adolescence represent a significant prediction for physical activity in adulthood. However, the relationship is very low, and, in some cases insignificant." This study found stronger correlations between physical activity in adolescence and 12 years later in adulthood (r=0.21 to 0.26) than from age 9 to age 21 (r=-.01 to 0.15). The effectiveness of increasing activity behavior in adolescence as an antecedent to improving adult activity has not yet been examined. Tracking of physical inactivity may be more impressive. One study reported that the probability of an inactive 12 year old remaining sedentary at age 18 years was 51-63% for girls and 54-61% for boys. Strategies for Promoting Activity in

Adolescents

Given that physical activity needs to be

promoted as a life-long continuum, it is apparent that different age groups

require separate strategies for promoting regular habits of activity. In all

groups, however, creating an enjoyment of physical activity in which individuals

can be successful and receive peer & family support is

key.

Strategies for health promotion are best formulated around recognized age-specific determinants of such activity. Research among adolescents has indicated a number of factors that have been associated with involvement in physical activity in this age group (Table 2). In general these center around opportunities for play, support of friends, and competence in physical activities. It is apparent, too, that the varying influences of cultural group, socioeconomic status, race, geography, and season must be considered when formulating interventional programs Table

2.

Psychosocial Factors Associated With Physical Activity in Adolescents.

It is possible that the factors which threaten

to diminish physical activity habits during adolescence can be utilized instead

as means of exercise promotion. For example, the educational message that the

individual can and should accept responsibility for his or her own health (and

exercise habits) is consistent with the adolescent's growing need for

independence. Similarly, providing the adolescent with a choice of activities

may prove more effective than physical education programs that dictate a

curriculum.

For instance, using community programs, it might be possible to offer a choice of activities such as rock climbing, in-line skating, or kayaking that would prove more appealing to the adolescent than traditional physical education programs. Taking a cue from anti-smoking programs, efforts could be made to make physical activities more attractive to teens as opposed to an unpleasant life of sloth (i.e., "it's cool to sweat"). Such efforts seem particularly pertinent to females, and the message that vigorous activity is important for girls needs to be continued to be emphasized. This can be supported through the promotional efforts of female athlete role models. If intramural sports cannot be made available within the school program, such activities should be developed by community recreation departments. The availability of school gymnasiums, exercise rooms, and pools in evening hours could be geared specifically to adolescent groups. The input of adolescents in creating such programs may be critical to their success. As the "consumers" of preventive efforts, cues as to what "works" may best come from the teenagers themselves. Providing them independence in formulating physical activity programs may also provide a means of increasing participation. Conclusion

A unique combination of biological and psychosocial factors coincide during adolescence to create a particular importance for health-related physical activity. At the same time, many of these factors provide barriers to stimulating teenagers to adopt regular exercise habits. Innovative physical education programs and exercise promotional efforts specifically directed to this age group are important in overall preventive medicine strategies. Success in these programs may hinge on the ability to utilize characteristics of this age group-need for independence, peer acceptance, desire for choice and variety-in formulating exercise initiatives. |

|

|

|

||

|

|

|

|